Annie Schiffer, Utah State University, discusses her article: The importance of accounting for spatial heterogeneity in studies of plant competition and coexistence

Our paper explores how ignoring spatial environmental heterogeneity produces biases in competition and coexistence models. The original motivation for this study was to explain why interspecific competition was underestimated in observational studies of plant coexistence, compared to experimental studies – which we failed to do.

We’re a group of theoretical and empirical ecologists, and we were following the conversation in the species coexistence literature about the many pitfalls when fitting coexistence models. Adler et al. (2018) and Tuck et al. (2018) found inconsistent strengths of interspecific competition in observational vs. experimental studies, and we intended to figure out the mechanism.

Spatial environmental heterogeneity: An influential but often unmodeled variable

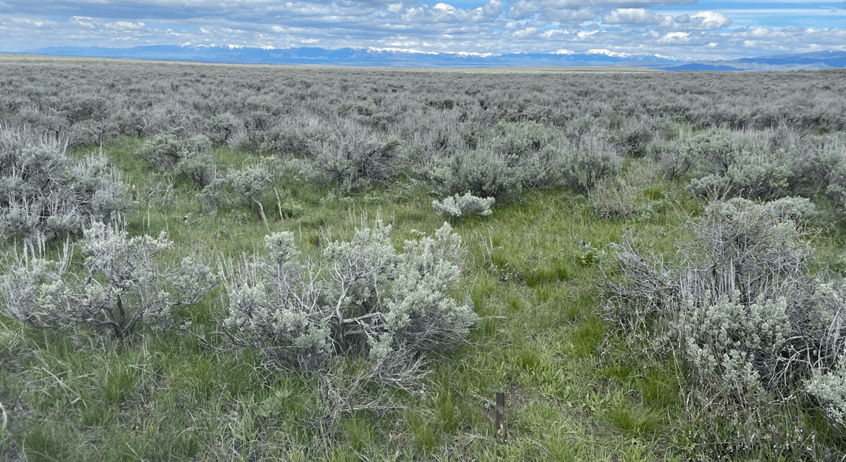

We suspected that ignoring spatial patterns resulting from environmental heterogeneity might be the explanation. You may be wondering, if environmental heterogeneity is influential, wouldn’t it be difficult to ignore in our models? Wouldn’t the spatial patterns in the plant community be obvious? Yes, it’s likely easier to account for spatial heterogeneity in systems where it’s obvious. For example, many studies have shown how light gaps in forests affect demography. In arid ecosystems, shrubs are fertile islands and can determine the distribution of soil resources.

But the underlying environmental heterogeneity and resulting spatial patterns aren’t that obvious in most communities. Even if the spatial patterns are obvious and spatial heterogeneity is modeled explicitly, environmental conditions (like light gaps) are often measured at the plot level, while demographic responses are measured at the individual level. We predicted that ignoring individual responses to environmental conditions would bias model estimates.

Consequences for competition and coexistence studies

We got the first simulation results and saw the opposite of what we expected: spatial heterogeneity caused intraspecific competition to be underestimated in simulated observational studies. We realized this wasn’t the mechanism behind the Adler et al. (2018) and Tuck et al. (2018) results, but we were onto something else.

We found that when environmental heterogeneity strongly affected individual plants (i.e. there are good and bad patches within a plot) but we ignored these effects, we underestimated intraspecific competition, overestimated interspecific competition, and incorrectly predicted competitive exclusion instead of coexistence. This was especially true in simulated observational studies compared to simulated short-term experiments. Our results indicate that ignoring the effects of environmental heterogeneity on individuals in neighborhood competition models will lead to biased conclusions about coexistence.

Where do we go from here?

This is our call to empirical ecologists: if you suspect that within-plot environmental heterogeneity is strong in your system and you’re fitting a neighborhood competition model, you should account for the effects of the environment on individuals, otherwise you may get the wrong answer. As an empirical ecologist myself, I know this is a hard thing to ask for. How are you supposed to know if spatial heterogeneity has strong effects on demography and which environmental variables to measure? We suggest either explicitly measuring environmental variables that seem influential or inferring the spatial patterns from demographic data. Ultimately, our study provides an explanation (though not the explanation we expected!) for the challenges that empirical ecologists are facing to accurately predict species coexistence in plant communities.