Rose Brinkoff and Olivia Vought, University of Michigan, discuss their article: The impact of warming on peak-season ecosystem carbon uptake is influenced by dominant species in warmer sites

Ecosystems both absorb and release carbon. Carbon dioxide gas (CO2) in the atmosphere is taken up by plants through the process of photosynthesis and released by plants and soil through respiration. The balance between these processes determines the net amount of carbon that is exchanged between the ecosystem and the atmosphere, known as net ecosystem carbon exchange (NEE). The NEE may reveal that there is a net uptake of carbon by the ecosystem (more photosynthesis than respiration) or net release of carbon (more respiration than photosynthesis).

Global temperatures are rising, and warming temperatures tend to lead to an increase in both photosynthesis and respiration; however, one is often higher than the other. This is because other factors, such as soil moisture, influence these processes. The interplay of warming and these other environmental factors makes it very difficult to predict the balance of carbon uptake and release from ecosystems in a changing climate.

Warming not only directly affects the balance of carbon uptake and release but also results in changes to species’ geographic ranges. This means that in a given area, the abundance of some plant species will increase and some will decrease, as new species move in and others become less abundant or locally extinct. Species’ rates of photosynthesis and respiration, and the responses of these processes to warming temperatures, vary widely. Thus, the shuffling and reassembly of plant communities adds another layer of complexity to predicting ecosystem carbon fluxes as the climate warms.

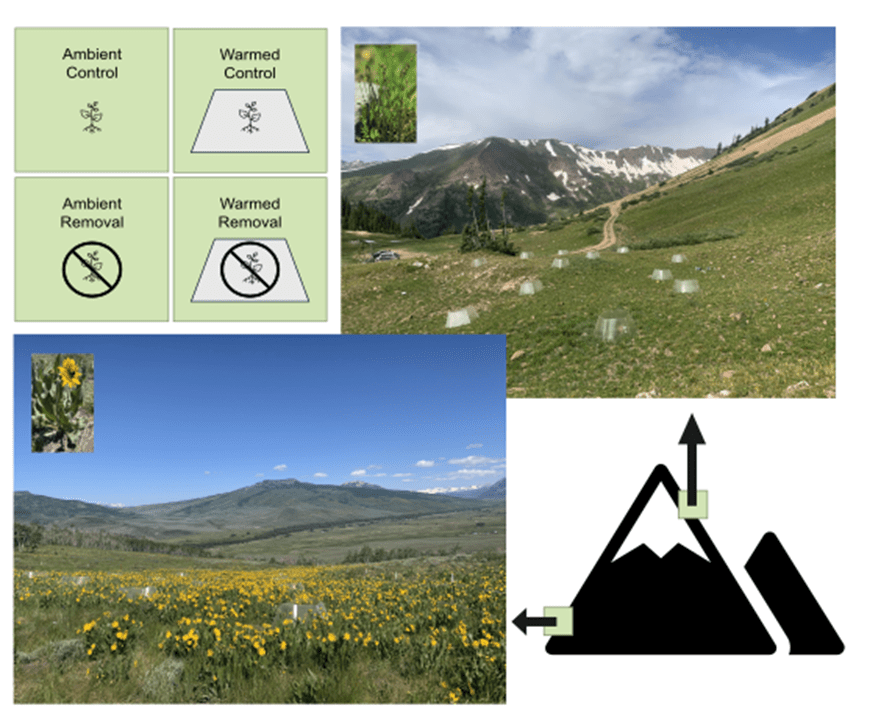

For our study in the Colorado Rocky Mountains, we simulated warming temperatures by installing clear, plastic, open-topped chambers to half of 32 2 x 2 plots. The chambers work in a similar way to a greenhouse – incoming radiation from the sun enters the chamber where it is trapped and reflected back towards the plants and soil, warming the temperature of the air inside by about 1.5 °C. In half of the warmed plots and half of the unwarmed plots, we altered the plant community by removing the aboveground part of the dominant species during the growing season. This experimental design allowed us to test the effects of warming and removal of the dominant species both separately and in combination. We replicated this experiment at two elevations (~2700 m and 3500 m).

Each year from 2015-2023 (with the exception of the COVID-19 year and a year where there was a surprise avalanche!), we measured NEE in each plot at the peak of the growing season. To measure NEE, we used a gas-analyser to measure the rate of change in the concentration of CO2 inside a clear plastic chamber which was sealed over each plot. These are not to be confused with the open-topped warming chambers; we took those off temporarily to perform the measurements. We also measured NEE with the chambers covered by a thick black cover – allowing us to measure respiration (no light = no photosynthesis, but respiration continues) and subtract this from NEE to calculate photosynthesis. With this information, we partitioned the net carbon flux into its components, photosynthesis and respiration, revealing more about the processes underpinning the response of NEE to the treatments we imposed and at the different elevations.

At the lower-elevation site, we found that warming increased net carbon uptake by increasing rates of photosynthesis, but only in plots where the dominant species was still present. Conversely, removing the dominant species decreased net carbon uptake (through a reduction in photosynthesis), and this effect tended to be stronger in warmed than ambient plots. This highlights the fact that the effect of warming on carbon uptake depends largely on the composition of the plant community, and the direct effects of warming can interact with the indirect effects of changes in species composition. We found no effects of either treatment at the high-elevation site. This was a surprise to us, because we expected that warming should have more of an effect in a cooler place than a warmer one. However, we found that the high-elevation site was resilient to both warming and removal of the dominant species.

Another interesting result from this study was that, in some years, the low-elevation site shifted from a net uptake to a net release of carbon – i.e., it emitted more carbon that it absorbed. A net release of carbon was particularly common in dry years, which could become more frequent in the future as drought frequency and severity is increasing across the world. This has important implications for climate change because it creates a positive feedback loop where warming increases carbon release, which in turn increases atmospheric CO2 and worsens the greenhouse effect.