Donghao Wu, from the Zhejiang University in China, discusses their article: The intrinsic coordination of tree growth strategy and wood decomposability

What happens after a tree dies?

As plant ecologists, we often focus on how trees grow: how fast they capture carbon, how tall they become, and how long they live. But forests are not only shaped by living trees. A substantial part of the carbon story unfolds after death, when wood decomposes and returns carbon to the atmosphere, soil, and food webs. This simple question—do fast-growing trees also decompose faster after they die?—was where our study began.

A hunch born in the forest

Our work took place in a 50-hectare subtropical forest plot in southern China, where hundreds of tree species coexist. Walking through this forest, the contrast among species is striking. Some trees grow rapidly, racing upwards to capture light. Others grow slowly, investing in dense wood and long lifespans.

Ecologists already know that these growth strategies matter for forest carbon uptake while trees are alive. What remained unclear was whether these strategies also leave a signature in the afterlife of trees—specifically, in how quickly their dead wood decomposes.

We suspected they might. Fast-growing species usually produce lighter, less dense wood, which is often easier for decomposers—especially termites—to consume. Yet this idea had rarely been tested directly across many tree species using real demographic data rather than a handful of wood traits.

Turning growth records into decay experiments

To test this idea, we combined two very different sources of information.

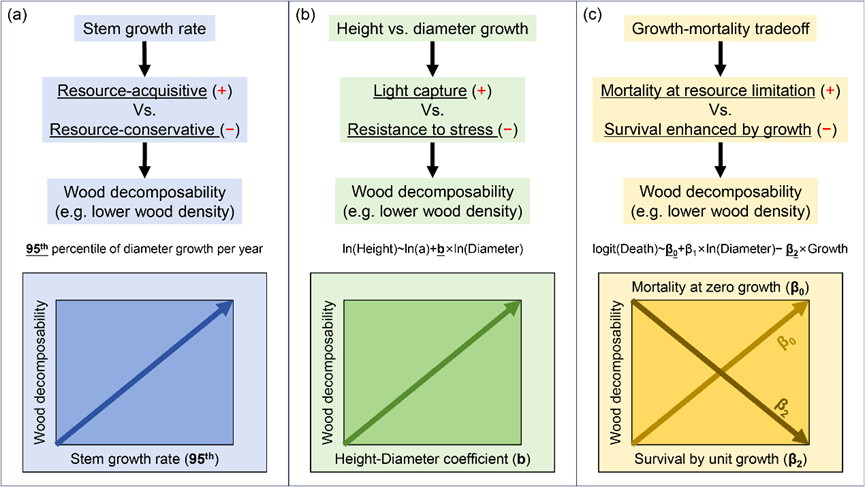

First, we drew on long-term forest census data. For each of 120 tree species, we quantified how fast trees can grow under favourable conditions, using the upper end of observed stem growth rates. This metric captures a species’ growth strategy rather than the performance of individual trees.

Second, we conducted a large field decomposition experiment. We placed branch samples from each species on the forest floor across valleys, ridges, and hilltops, and measured wood mass loss after 8 and 16 months. We also recorded whether termites had colonised each piece of wood.

This allowed us to ask a simple but powerful question: does how fast a tree grows predict how fast its wood decays?

Fast growth, fast decay

The answer was a clear yes.

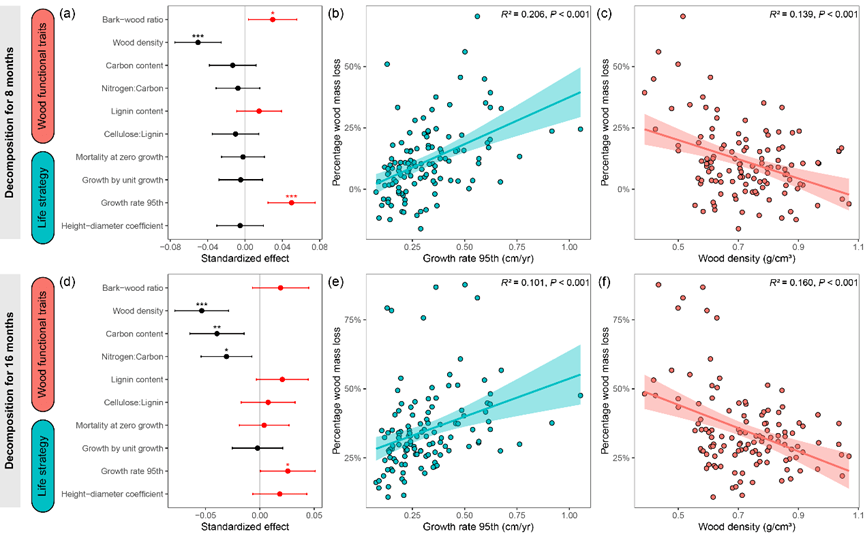

Wood from fast-growing species decomposed more quickly than wood from slow-growing species, particularly during the early stages of decay. In fact, growth rate explained more variation in early decomposition than classic wood traits such as wood density.

One key reason was termites. Wood from fast-growing species was more likely to be colonised by termites, the dominant wood decomposers in this forest. Termite activity strongly accelerated decomposition, effectively linking growth strategies aboveground with carbon release belowground. At later stages of decay, wood traits such as density became equally important. Still, the overall message remained robust: tree growth strategy and wood decomposability are intrinsically linked.

Why this matters for forest carbon cycling

Dead wood stores about 8% of global forest carbon. Whether this carbon remains locked up for decades or is rapidly released depends on how fast wood decomposes.

Our findings suggest that increases in forest productivity—driven by climate change, rising CO2, or management—may not automatically translate into long-term carbon storage. Faster tree growth can be accompanied by faster turnover, through both shorter lifespans and quicker deadwood decay.

In other words, forests may operate with tighter internal checks and balances than we often assume: more carbon captured, but also more carbon released.

Looking ahead

One promising implication of this work is practical. Tree growth rates can be estimated from forest inventories worldwide, including those from ForestGEO and the Global Forest Biodiversity Initiative. If growth strategy reliably predicts wood decomposition, we gain a new way to link living forests with their afterlife processes—without measuring every possible wood trait.

For me, this study has changed how I walk through forests. Fallen logs are no longer just remnants of past growth; they are echoes of a tree’s entire life strategy. How a tree lives shapes how it dies—and how quickly it returns its carbon to the world.