Zoe Loffler tells us about her recently published article in Journal of Ecology…

Severe storms and cyclones can have devastating effects on coral reefs, breaking and dislodging corals. Recovery from such events can be prolonged, especially in instances when the reef is overgrown by large fleshy seaweeds. But how do cyclones and storms affect the abundance of seaweeds on coral reefs? Could these storms similarly reduce the abundance of unwanted seaweeds, and provide a window of opportunity for the recovery of corals?

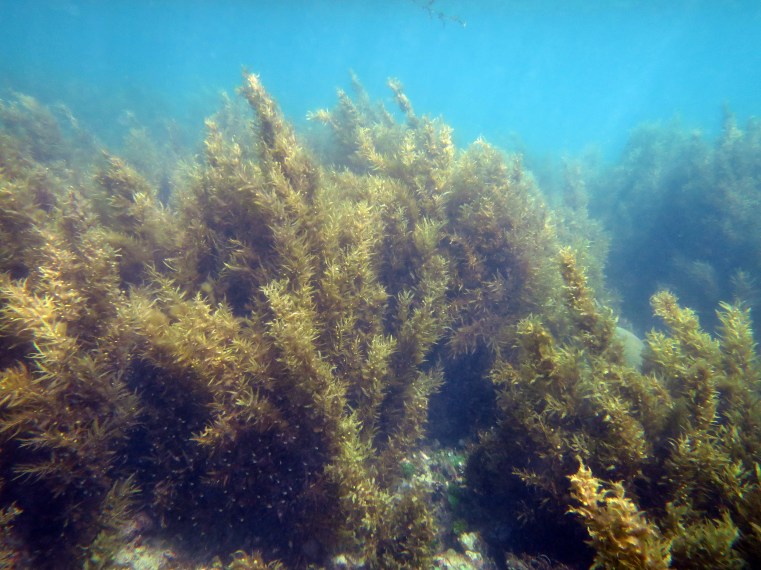

Sargassum is a tall, brown, fleshy seaweed that grows to dominate many degraded coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific ocean. Once established, these Sargassum beds are difficult to remove, inhibiting the return to a coral-dominated ecosystem. This prompted us to consider what role, if any, storms and cyclones could play in mitigating the growth and abundance of unwanted seaweeds on degraded coral reefs.

Sargassum dominates many degraded coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific ocean

In this new study published in Journal of Ecology, we examined if storms, which often break off tall seaweeds at the base of the stipe (‘stem’), could help to reduce seaweed abundance on coral reefs. Using Sargassum spp. beds located at Orpheus Island, on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, we simulated the effect of a severe storm and tracked the bed recovery over an eleven-month period.

Surprisingly, we found that cutting the Sargassum off at the base of the stipe (simulating the effect of a severe storm) had no lasting effect on the height, density or biomass of the seaweed after a period of 5-11 months. This is due to the remarkable ability of the seaweed to regrow from its holdfast (‘root’). In contrast, areas where we also removed the holdfast, the density and biomass of the seaweed was reduced by 50% over the same period.

Given the apparent importance of the holdfasts to seaweed resilience, we then investigated if herbivorous fishes could remove holdfasts while they forage. To answer this question, we exposed some holdfasts to local herbivores and protected others within cages, and followed the persistence of holdfasts over time.

Lead author Zoe Loffler measuring Sargassum

The study revealed that herbivores, most likely parrotfish, reduced the number of Sargassum holdfasts on the rocks by 70% over four months as compared with caged rocks that the herbivores could not access. This was likely due to the feeding behaviour of parrotfish, which use their strong, beak-like jaws to scrape algae, detritus and associated microbes from the reef.

These findings emphasise the resilience of Sargassum seaweed beds to disturbance, and suggest that severe storms or cyclones alone are unlikely to have any lasting impact on the abundance of Sargassum on coral reefs. If a storm is to help reduce the abundance of Sargassum on a coral reef, and therefore make space for corals to grow, it must occur in conjunction with an increase in the herbivores capable of removing holdfasts from the reef.

With the current push toward more interventionist approaches to reef management, efforts to manually remove seaweed are becoming more common. This study highlights that such initiatives must ensure that the holdfast of the seaweed is completely removed. Any holdfasts left intact on the reef will allow the seaweed to rapidly grow back to its previous abundance.

Zoe Loffler, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University, Australia

Read the full paper: Canopy-forming macroalgal beds (Sargassum) on coral reefs are resilient to physical disturbance